The "KCL and the Foundations of Modern Genetics" is the new project blog of Kings College London Archives on the digitisation of the combined papers of Maurice Wilkins (1916-2004) and the King’s Biophysics Department. This project is funded by the Wellcome Trust and is one of many collections selected for digitisation into the Wellcome Digital Library under the theme of “Modern Genetics and its Foundations”.

Monday 1 October 2012

DNA and Social Responsibility: Raymond Gosling: Flickr set dedicated to PhD thesi...

DNA and Social Responsibility: Raymond Gosling: Flickr set dedicated to PhD thesi...: Following the successful digitisation of Raymond Gosling's PhD thesis, 'X-ray diffraction studies of Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid' I have add...

DNA and Social Responsibility: Raymond Gosling: Visit to King's Archives

DNA and Social Responsibility: Raymond Gosling: Visit to King's Archives: A few months ago, I had the pleasure of meeting Professor Raymond Gosling as he came into the Archives to be interviewed for a Swedish do...

DNA and Social Responsibility: Raymond Gosling: Not just an extraordinary envoy

DNA and Social Responsibility: Raymond Gosling: Not just an extraordinary envoy: Raymond Gosling was one of the key workers on DNA at King's during the period that became immortalised as the 'Race for the Double Hel...

Friday 7 September 2012

DNA and Social Responsibility: Not another conference: A letter from Sir Nevill M...

DNA and Social Responsibility: Not another conference: A letter from Sir Nevill M...: While trawling through the papers relating to political activism it is difficult it is difficult to keep track of the myriad political gro...

Wednesday 5 September 2012

Digitising X-rays: the digitisation of the Biophysics collection

In this week’s post, I discuss some of the digitisation

aspects of the project with special reference to the work of one of our

digitisation contractors, MAX (previously MAX COMMUNCATIONS,) who digitised 4,000

of the glass and acetate material.

In October 2011, two of the digitisers from Max Ltd visited the archives in order to

familiarise themselves with the collection and carry out some test scanning.

The material was quite diverse: photographic prints, x-ray acetates, various

sizes of glass plate negatives, folded negative rolls and 35mm mounted slides.

The majority of this material required external specialists with the required

expertise and equipment to undertake the scanning. A small test file was

created composed of quarter plate glass negatives and x-ray acetates and sent

to the Wellcome for approval. Both Iain Stringer, who would go on to digitise

the collection, and David Cordery, head of Max

Ltd, have prior professional experience of working with glass plate and

acetate x-ray collections at various institutions around the UK and we were fully confident of

their ability to handle the fragile items and successfully scan them. The test

images that were sent to the Wellcome were approved and scanning commenced in

December 2011.

The images were

scanned at 300 dpi (dots per inch) at 8-bit (bit rate) RGB (Red Green Blue)

using an Epsom V750 Pro scanner. This type of flatbed scanner is reliable and

fast and from a preservation perspective, the scanner was suitable for digitising

the x-ray acetates as the two- inch gap between the bed of the scanner and the

top scanner head meant that it did not press onto the x-rays and so would not

cause any further damage to the x-rays afflicted with vinegar syndrome (vinegar

syndrome occurs when an acetate degrades and begins to oxidise creating a

vinegar smell. The surface often begins to warp and crack and this eventually

affects the emulsion. Unfortunately the process is irreversible and it is why

digitisation is one of the most effective ways of preserving an accessible copy

of the item.)

I asked Iain to tell me about his experience scanning our

material compared to his previous experience with similar collections. He said

that the plates, in terms of general condition, were some of the best that he

has worked with as hardly any were chipped or broken. The only slight issue

that he encountered was that some of the slides were mounted with red strips,

the adhesive of which had begun to seep and caused them to attach themselves to

their transparent sleeves. In such cases, he therefore had to carefully remove

the slide from its sleeve. This required a degree of perseverance, depending on

the age and location of the adhesive strips on the slide.

Regarding the x-ray acetates, I had assumed that this

material would be trickier to scan considering the conditions that some of them

were in. Iain surprised me by saying that for the purposes of scanning they

were quicker to scan than the glass plates. Whilst care had to be taken in

handling small, fragile and brittle objects like deteriorating x-ray acetates,

the most time consuming element of scanning an x-ray was the post-production.

MAX Ltd provided us with images in three formats: the raw TIFF original file, the enhanced TIFF

amended file and a JPEG file. While enhancing an image can be difficult with

regard to obtaining an authentic copy of the original, in a situation where the

original is difficult to discern, post-production ‘clean up’ is necessary. The

majority of the x-ray acetates retained a degree of visible content and by

using Adobe Photoshop post production, it made it easier to enhance the original

pattern of the x-ray and compensate for some of the surface damage caused by

any deterioration.

Finally, I asked Iain what he thought of the acetate and

glass material as a whole. He said:

“ I found the material

quite interesting…I’ve learnt more about DNA than I have since school,, good

thing about my job that I don’t have to concentrate on one specific thing.

X-rays of DNA, diffraction, very interesting. They would definitely make a good

print, stretched over a canvas, especially one of the really clear ones like

‘Photo 51’”

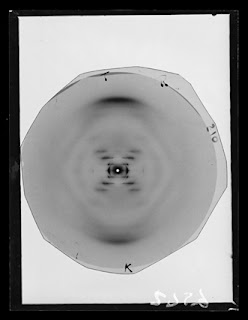

I agreed, diffraction patterns such as ‘Photo 51’ are

visually striking though I personally am more in awe about the crystalline

A-form DNA pictures as there is something rather mesmerising about the symmetry

of these patterns. You can judge for yourself however, as these two x-ray

patterns are shown below.

|

| A-form DNA |

Sunday 19 August 2012

Will the archives of the future be made of the strand of DNA?

The prospect of combining archives and DNA feels like a plotline of a Twilight Zone episode. What's exciting however is that it is a distinct possibility. The Guardian have just released a story about the DNA inscription of a book ( http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2012/aug/16/book-written-dna-code) initially reported in the US journal, Science. The book composed of 53,000 words includes eleven images and a computer program. The 5.27 megabit collection of data created over several days was produced by Professor George Church of Harvard Medical School.

The method they used, in principle, was the same as digital inscription: encoding all the book information into a binary sequence. The DNA base pairs in this case representing 1's and 0's with Arginine (‘A’) and Cytosine (‘C’) representing zero, and Guanine (‘G’) and Tyrosine (‘T’) representing one. The team developed a system in which an inkjet printer embeds short fragments of artificially synthesized DNA onto a glass chip. Each DNA fragment contains a digital address code that denotes location within the original fiDNAle.

What makes DNA such a brilliant medium for storage is its data storage with estimates suggesting a gram of DNA can store 455 billion gigabytes. The data is easily readable and copied and maintains its stability for several thousand years.

The possibilities are fantastic. To put this in perspective, most digital formats require an upgrade after five years with physical data storage such as DVDs having, at most, a twenty year life span. This is because of the constant change in informational software packages within sturdy digital formats, such as TIFFs and PDFs having 10-15 year maximum life span. A DNA code sequence is therefore more desirable than a digital approximate, but neverless it is an exciting development and will potentially rival the paper record revolution in record keeping. This is an exciting archival perspective.

As a cataloguer and digitiser of the DNA related material of the Kings college London archive such a development is one of a personal joy. It would feel wonderfully apt to have the papers charting the discovery of the structure of DNA are encoded into DNA for future generations.

The method they used, in principle, was the same as digital inscription: encoding all the book information into a binary sequence. The DNA base pairs in this case representing 1's and 0's with Arginine (‘A’) and Cytosine (‘C’) representing zero, and Guanine (‘G’) and Tyrosine (‘T’) representing one. The team developed a system in which an inkjet printer embeds short fragments of artificially synthesized DNA onto a glass chip. Each DNA fragment contains a digital address code that denotes location within the original fiDNAle.

What makes DNA such a brilliant medium for storage is its data storage with estimates suggesting a gram of DNA can store 455 billion gigabytes. The data is easily readable and copied and maintains its stability for several thousand years.

The possibilities are fantastic. To put this in perspective, most digital formats require an upgrade after five years with physical data storage such as DVDs having, at most, a twenty year life span. This is because of the constant change in informational software packages within sturdy digital formats, such as TIFFs and PDFs having 10-15 year maximum life span. A DNA code sequence is therefore more desirable than a digital approximate, but neverless it is an exciting development and will potentially rival the paper record revolution in record keeping. This is an exciting archival perspective.

As a cataloguer and digitiser of the DNA related material of the Kings college London archive such a development is one of a personal joy. It would feel wonderfully apt to have the papers charting the discovery of the structure of DNA are encoded into DNA for future generations.

Tuesday 7 August 2012

August Project Update

The project is entering its final months and a quick update as it what has been happening is in order:

To date, 24,000 images have been produced by our digitisers which roughly breaks down as 4000 glass plate and acetate images and 20,000 images from the paper collection. Over the next two months the remaining part of the paper collection will be scanned. Sections that have already been scanned include papers from Wilkins’ early life, scientific working papers, correspondence with scientific colleagues, papers associated with the history of the research on DNA and sections of his autobiography.

Above, is a low resolution copy of some of the images that are being produced. The example is a postcard received by Maurice Wilkins from Francis Crick dated May 1955 and sent from Paris. The postcard reads: "Having a lovely time telling people about your work and my ideas! Hoping to see you in Cambridge for a quiet weekend - Francis".

Our main tasks over the next few months involve the construction of metadata and copyright and sensitivity checking. The latter is the most time consuming as a detailed survey requires a systematic check of all potentially risky material. Our catalogue descriptions are written at a level to summarize the contents of the physical file but because the images will be accessible individually an item level approach to sensitivity and copyright is needed to be certain that legally and ethically all necessary precautions are taken before publishing on-line. Needless to say this process is time-consuming and has proved to be the most taxing element of the project.

Apart from the construction of metadata and the sensitivity checking the only other main strand of the project to update everyone with is outreach. The project continues to gather interest from its social media sites (like the one I’m writing on now). Besides the blogs, the project has had a presence on Twitter and new images have been added to the project’s Flickr site. In May, the archives participated in a Radio 4 piece on the Wellcome Digital Library which was reported previously on this blog. Alongside this, we were privileged to have been visited by Raymond Gosling in March as part of a television documentary. It was wonderful to meet a contemporary of Wilkins and Franklin and hear from one of the key workers his own experience working at King’s at the time. We are quite fortunate to have a copy of Gosling's original 1954 PhD thesis, titled ''X-ray diffraction studies of Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid' which has been selected to be digitised as part of the King's College London Biophysics collection.

Friday 27 July 2012

New Flickr set of Glass Plate negative images

A new Flickr gallery showing some of the images that have been included in our current digitisation project is now available. The images have been selected from the glass plate negative series (KDBP/1/1) which contain a number of images documenting x-ray diffraction and other physical studies into DNA. The series dating from 1949 to 1984 contains significant landmark diffraction patterns of DNA including early crystalline A-and semi-crystalline B-forms in particularly 'Photo 51' created by Rosalind Franklin. Along with x-ray patterns there are also model representations of the structure and graphical representations of the King's team's findings.

The new Flickr set can be found in the link below:

Friday 13 July 2012

The Library of Maurice Wilkins: Part 2

|

The Atomic Spies by H Montgomery Hyde, 1981: This book focuses

on the British-based spies who provided the USSR with information relevant for

the construction of an atomic bomb. Wilkins had links with two of the convicted

men. He knew Klaus Fuchs at Birmingham University, and was friendly with the

family of Allan Nunn May. He did not however know that he himself was also

investigated by MI5 as a potential atomic spy from 1951-1954 (see previous blog

post for more information: http://dnaandsocialresponsibility.blogspot.co.uk/2010/08/maurice-wilkins-accused-of-spying-by.html).

|

The Library of Maurice Wilkins Part 1

'A personal library is an X-ray of the owner’s soul. It offers keys to a particular temperament, an intellectual disposition, a way of being in the world. Even how the books are arranged on the shelves deserves notice, even reflection. There is probably no such thing as complete chaos in such arrangements.'

Jay Parini, American writer and academic (b 1948-)

As part of the acquisition of Maurice Wilkins personal papers for the King’s College London archives, the family also donated an extensive part of his private library. This generous gift contains a plethora of non-fictional material ranging from his scientific career in biophysics to later work in nuclear disarmament. The collection, consisting of books, booklets, pamphlets and journal articles, can be found within the Archives Reading Room in the Strand Building and occupies ten shelves. As the above quotation states, a personal library can be a window to the owner’s soul and the Wilkins library collection certainly conveys a sense of Wilkins’ range of interests.

The collection contains journal articles and leaflets from a number of publications. Some relate to his scientific career with off-prints from the Journal of Molecular Biology, while others reveal his interest in the relationship between art and science. Also included are a series of annual booklets from the Nobel Prize organisation, listing prize winners.

The published books cover a diverse number of subjects but can be broken down into the following categories:

Science: life sciences, genetics, physics and biographical material

History: mainly the history of science, but also of ancient Greece, the Renaissance and the political and scientific history of the twentieth century

Psychology and Philosophy: psychoanalysis and how the mind works, also alternative therapies and eastern philosophy, in particular the practice of yoga

Anti-nuclear: relating to the anti-nuclear movement, disarmament, nuclear conflict.

Friday 22 June 2012

Anyone for Vegetarian Athletics?

|

| The Vegetarian Brothers |

Whilst, trawling through the autobiographical section of the personal papers of Maurice Wilkins I came across a remarkable pamphlet,"Vegetarian Athletics (What they prove and disprove)" by Henry Light, produced by the Vegetarian Society, features the semi-naked vegetarian wrestling champions, S V and E H Bacon mid-bout.

The pamphlet was part of the collected papers of Edgar Wilkins, Maurice's father, who was himself a committed vegetarian and keen exerciser. Trained as a doctor at Trinity College Dublin, he later concentrated on public health and preventative medicine and had a life long interest in the effects of diet and exercise on health. His papers were collected as part of Maurice Wilkins' autobiographical research, originally to provide the reader with a framework of how family characteristics were passed down through the generations.

The twelve page pamphlet makes interesting reading not only through its content but its wonderful use of language especially when describing non-vegetarians as "flesh-eaters" or lines such as "before coming a vegetarian he was an epileptic". It provides examples from recent times of world and national record holding vegetarian athletes similar to the wrestling brothers on the front. In some cases it provides a detailed break down of their diet such as Eustace Davies, mountain climber:

"Whilst training, except when visiting friends, his food consisted chiefly of:

Breakfast: Bread and butter, hot milk, potato, green salad and oil, and sometimes an egg.

Lunch and dinner: Cheese, Bread, butter, potatos, green salad and oil, milk-pudding, and stewed fruit and cream.

The food used during the performance itself was principally of a liquid nature. For the first ten hours it was egg and milk. Thereafter milk and soda, lemon water, some tea and egg, and once or twice milky tea at inns in the valleys. Also stewed fruit and cream and milk pudding at three places; and two oranges."

Davies was quoted by the author saying: "I owe you a great debt of gratitude; your advice was acted upon in toto, and I do not know of any other system of feeding on which I could have done the trick".

The pamphlet is interspersed with general advice on the merits and practicalities of vegetarianism and also the initial difficulties a former "flesh-eating" athlete might encounter when he first switches to vegetarianism. Henry Light at one point warns: "Before starting on a vegetarian system of living, one should be thoroughly convinced not only of its superior ethical value but its practicability, and be thoroughly determined after starting, for the mind has so great an influence over the body that the slightest wavering or doubt usually spells failure, and failure of course brings discredit upon the cause and oneself".

Wednesday 16 May 2012

Wellcome Digital Library Project featured on BBC Radio 4 "Today" programme

The Wellcome Digital Library project was today featured on BBC Radio 4's "Today" programme. The report by Fergus Walsh, medical correspondent of the BBC featured recordings from King's College London, Wellcome Trust and Churchill Archives, Cambridge. The report centered on the archives relating to the critical discovery of the structure of DNA and the contributions of Crick, Franklin, Watson and Wilkins respectively.

The report can be heard on the BBC iPlayer (for those based in the UK) for the next week and starts at the 02:50 mark until 02.55. (http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b01hjs46/Today_16_05_2012/) or is available on the Today programme website (http://news.bbc.co.uk/today/hi/today/newsid_9721000/9721286.stm).

In the visit to King's, Fergus Walsh was given a tour of our principle vault and shown "Photo 51" alongside a number of other items in the joint Maurice Wilkins/Biophysics collection. Some of these images can be seem on his blog post (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-18041884).

For our partner institutions, a photo gallery of Crick correspondence from the Wellcome Trust collection was put up on the BBC Today programme home page (http://news.bbc.co.uk/today/hi/default.stm).

The report can be heard on the BBC iPlayer (for those based in the UK) for the next week and starts at the 02:50 mark until 02.55. (http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b01hjs46/Today_16_05_2012/) or is available on the Today programme website (http://news.bbc.co.uk/today/hi/today/newsid_9721000/9721286.stm).

In the visit to King's, Fergus Walsh was given a tour of our principle vault and shown "Photo 51" alongside a number of other items in the joint Maurice Wilkins/Biophysics collection. Some of these images can be seem on his blog post (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-18041884).

For our partner institutions, a photo gallery of Crick correspondence from the Wellcome Trust collection was put up on the BBC Today programme home page (http://news.bbc.co.uk/today/hi/default.stm).

Maurice Wilkins and the ultrasonic pursuit of the mechanisms of life

The scientific career of Maurice Wilkins did not solely focus on the structure and refinement of DNA. Having begun reading Physics at Cambridge in 1936, Wilkins went on to work on luminosity and phosphorescence and made contributions to wartime radar research in Birmingham and later at the University of California, Berkeley, on the Manhattan Project to develop the first atomic bomb. After reading Erwin Schrödinger’s seminal “What is Life?” (1944), which influenced a generation of scientists, and following a period of soul-searching following the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Wilkins decided to focus his research on biophysics – the use of physics to study biological structures. He began his work by investigating the effect of ultrasonics on chromosomes.

Wilkins’ began research on the biological implications of ultrasonic technology when he first moved back to the UK after his wartime experience in America. Whilst at St Andrews, he was talking to the Glasgow University-based geneticist, Charlotte Averback, about Hermann Muller’s work using x-rays to cause mutations within fruit flies and he wondered whether he could replicate it using another physical agent. As Wilkins states in the The Third Man of the Double Helix (2003):

“No-one seemed to have tried strong high frequency sound (ultrasonics) on chromosomes...it was a way of starting [in biophysics]; I could do it on my own and it might help us to understand how genes worked” (p91)

The aim of his experiments was to explore the effects of ultrasonics on a living cell nucleus and especially its effect on the process of mitosis. The hope was that the ultrasonics ray would cause breakage of the chromosome and provide an interesting comparison with similar breaks engendered by other agents such as x-rays.

The initial experiments typified Wilkins’ approach to science, as he constructed by himself a high power ultrasonic generator for the experiments. A paper produced by G G Selman and Wilkins published in July 1949, states that their high intensity ultrasonic apparatus could “generate and measure higher unfocused ultrasonic intensities than any we have yet found recorded in the literature” (p229, G. G. Selman & M. H. F Wilkins, "The production of high intensity ultrasonics at megacycle frequencies” in Journal of Scientific Instruments, Volume 26).

Yet results proved disappointing: no evidence of the cytogenetical effects of ultrasonics were found despite using an array of different samples including root tips, chick heart fibroblasts and Tradescantia pollen tubes.

Wilkins was soon keen to move onto other projects when he realised pursuing ultrasonics was not worthwhile and he was asked by John Randall to take over research into how DNA moved and grew in living cells. It was this shift into microscope studies of DNA that would lead Wilkins to recognise the potential of x-ray diffraction to elucidate the structure of the molecule.

Thursday 10 May 2012

Selecting Material for Digitisation: Glass Slides and X-ray acetates

Part of my role for the project is

to select relevant material from the Biophysics collection for digitisation.

The Biophysics collection of paper, glass plate and acetate photographic

material produced by staff members and spans from the department's inception in

1947, to 1984. My brief was to select a subset of 4000 images from this

collection relating to DNA research carried out by Maurice Wilkins and others.

The bulk of the images came from the quarter plate glass

plate negative collection that comprises of 18300 individual items. While DNA

research accounts for a significant proportion, other departmental work notably

on muscle and the structure of collagen are also represented. The DNA related

slides had to be handpicked from this larger total. Fortunately, the entire

series had been indexed by the department. During the cataloguing project in

2011, these index books were digitised and transcribed into a spreadsheet, which

made the task of selection much easier.

The selection criteria used was based on my own

understanding of the collection and the brief of the project. Having worked on

the cataloguing project of the papers prior to this role, I felt confident in

my ability to determine which material should be included. For the most part

this was fairly academic as each slide indicated who created them and all

material from well known DNA researchers was selected (e.g. Wilkins, Franklin,

Gosling, Wilson etc.). When the creators’ relationship to DNA research was not

so obvious, such as visiting academics or PhD students, then I consulted the

catalogue to see whether they collaborated in DNA research. I decided to

include all work (not just DNA research) in the early years of the department

as often related project techniques and microscopy work helped shape the later

DNA research. Supplementary material relating to microscopy studies, chemical

analysis and model building and a smaller number of half plate glass plate

negatives and photographic prints were also included.

The jewel in the crown so to speak was the third main source

of material - the x-ray acetates. Remarkably, some of the original x-ray

exposures have survived and capture the various samples, salts and techniques

that the KCL Biophysics department used in their x-ray diffraction studies of

DNA and later RNA and nuceleoproteins. It was decided early on that all the

x-rays were to be digitised, due in part due to their intrinsic value but

secondly because of their unstable physical condition. Acetate film has a

tendency to deteriorate and undergo what is known as vinegar syndrome. This is

when the acetate degrades and begins to oxidise creating a vinegar smell. The

surface often begins to warp and crack and fades the original image. The

condition is autocatalytic which means that once it has begun it cannot

be stopped with the only stabilisation solution being to isolate and freeze the

material. Many of the x-rays show the early signs of this condition (small pock

marks) but the vast majority have retained clear x-ray patterns.

|

| X-ray diffraction exposure showing clear warping and peeling of the emulsion layer but retaining the x-ray pattern of DNA. |

|

| X-ray diffraction exposure of DNA with typical pock marks associated with acetate deterioration |

Digitisation is the best strategy for long term preservation of this material for several reasons. Firstly, by producing a digital copy we can retain valuable content before further deterioration ensues. Secondly, the digital copy will be more accessible than the original as a high quality scan can provide a greater degree of clarity than the physical copy and thirdly by producing a digital surrogate it reduces the risk of damage from physical handling and allows for the original material to be put into cold storage.

Overall, the images selected from the Biophysics Department

are representative of the biophysical approach to genetics taken between

1947-1969.The collection provides an unprecedented record of x-ray diffraction

studies in genetics as well as fully documenting the experimental work of

Maurice Wilkins and his colleagues carried out at King’s.

Wednesday 7 March 2012

The digitisation of the papers of Maurice Wilkins and the KCL Biophysics Department

Welcome to the new archive project blog relating to the digitisation of material from the papers of Maurice Wilkins and the Biophysics Department. This project forms part of the major digitisation initiative by the Wellcome Trust to create a digital resource on the theme of “Modern Genetics and its Foundations”. The Wellcome Digital Library will provide digital access to its substantial genetics historical collections including the Francis Crick papers along with those of other partner organisations such as King’s. In particular, this project will bring together for the first time the papers of the four main protagonists in the discovery of DNA: Alongside the Wilkins and Biophysics Departmental papers of Kings College London will be the papers of the Francis Crick, James D Watson (Cold Spring Harbor) and Rosalind Franklin (Churchill Archive, Cambridge).

Altogether, King’s College Archives will provide over 31,000 images of archive material including:

- · KCL Department of Biophysics: glass plate and acetate x-ray images, 1949-1965

- · Papers of M H F Wilkins: relating to scientific research, 1948-1965, chiefly in DNA, including: notes on the various animal sources of the DNA samples used, laboratory notebooks recording the readings obtained the x-ray diffraction images, with related data set created on the IBM 650 computer and documents interpreting the DNA data, including graphs, Fourier transforms, Bessel Wave functions, sketches, calculations, measurements and diagrams.

- · Wilkins’ draft notes, 1955-1959, for presentations on progress of the Biophysics Unit’s DNA research

- · Research reports for the academic years 1954-55 and 1957-58, summarising the work to date on the structure of DNA, with additional manuscript notes

- · Wilkins’ contemporary correspondence with fellow DNA researchers and article co-authors, both UK and internationally, 1948-1968, including Francis Crick, Herbert Wilson, Leonard Hamilton, Boris and Harriet Ephrussi, and others, with comment on the progress of DNA research at KCL and elsewhere

- · Correspondence with and about James Watson, 1966-1969, detailing Wilkins’ negative response to draft versions of Watson’s autobiography, The Double Helix

- · Established draft sections of his autobiography, 1992-1994, countering accusations of sexism in his attitude towards Rosalind Franklin, and related published and unpublished material relating to Franklin, 1951-1999, including a copy of her experimental notebook on x-ray diffraction studies, annotated by Wilkins.

The blog site will provide an insight into the procedures and issues raised in digitising a large archival collection and follow on from the previous project blog, DNA and Social Responsibility (http://dnaandsocialresponsibility.blogspot.com/) by highlighting some of the documents we encounter during the course of the project and writing mildly amusing/interesting posts about the subject (this is our aim but it’s not a guarantee).

As a sign off I wish to illustrate some of the fantastic images that are being produced by the digitisation team.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)