The "KCL and the Foundations of Modern Genetics" is the new project blog of Kings College London Archives on the digitisation of the combined papers of Maurice Wilkins (1916-2004) and the King’s Biophysics Department. This project is funded by the Wellcome Trust and is one of many collections selected for digitisation into the Wellcome Digital Library under the theme of “Modern Genetics and its Foundations”.

Friday, 7 September 2012

DNA and Social Responsibility: Not another conference: A letter from Sir Nevill M...

DNA and Social Responsibility: Not another conference: A letter from Sir Nevill M...: While trawling through the papers relating to political activism it is difficult it is difficult to keep track of the myriad political gro...

Wednesday, 5 September 2012

Digitising X-rays: the digitisation of the Biophysics collection

In this week’s post, I discuss some of the digitisation

aspects of the project with special reference to the work of one of our

digitisation contractors, MAX (previously MAX COMMUNCATIONS,) who digitised 4,000

of the glass and acetate material.

In October 2011, two of the digitisers from Max Ltd visited the archives in order to

familiarise themselves with the collection and carry out some test scanning.

The material was quite diverse: photographic prints, x-ray acetates, various

sizes of glass plate negatives, folded negative rolls and 35mm mounted slides.

The majority of this material required external specialists with the required

expertise and equipment to undertake the scanning. A small test file was

created composed of quarter plate glass negatives and x-ray acetates and sent

to the Wellcome for approval. Both Iain Stringer, who would go on to digitise

the collection, and David Cordery, head of Max

Ltd, have prior professional experience of working with glass plate and

acetate x-ray collections at various institutions around the UK and we were fully confident of

their ability to handle the fragile items and successfully scan them. The test

images that were sent to the Wellcome were approved and scanning commenced in

December 2011.

The images were

scanned at 300 dpi (dots per inch) at 8-bit (bit rate) RGB (Red Green Blue)

using an Epsom V750 Pro scanner. This type of flatbed scanner is reliable and

fast and from a preservation perspective, the scanner was suitable for digitising

the x-ray acetates as the two- inch gap between the bed of the scanner and the

top scanner head meant that it did not press onto the x-rays and so would not

cause any further damage to the x-rays afflicted with vinegar syndrome (vinegar

syndrome occurs when an acetate degrades and begins to oxidise creating a

vinegar smell. The surface often begins to warp and crack and this eventually

affects the emulsion. Unfortunately the process is irreversible and it is why

digitisation is one of the most effective ways of preserving an accessible copy

of the item.)

I asked Iain to tell me about his experience scanning our

material compared to his previous experience with similar collections. He said

that the plates, in terms of general condition, were some of the best that he

has worked with as hardly any were chipped or broken. The only slight issue

that he encountered was that some of the slides were mounted with red strips,

the adhesive of which had begun to seep and caused them to attach themselves to

their transparent sleeves. In such cases, he therefore had to carefully remove

the slide from its sleeve. This required a degree of perseverance, depending on

the age and location of the adhesive strips on the slide.

Regarding the x-ray acetates, I had assumed that this

material would be trickier to scan considering the conditions that some of them

were in. Iain surprised me by saying that for the purposes of scanning they

were quicker to scan than the glass plates. Whilst care had to be taken in

handling small, fragile and brittle objects like deteriorating x-ray acetates,

the most time consuming element of scanning an x-ray was the post-production.

MAX Ltd provided us with images in three formats: the raw TIFF original file, the enhanced TIFF

amended file and a JPEG file. While enhancing an image can be difficult with

regard to obtaining an authentic copy of the original, in a situation where the

original is difficult to discern, post-production ‘clean up’ is necessary. The

majority of the x-ray acetates retained a degree of visible content and by

using Adobe Photoshop post production, it made it easier to enhance the original

pattern of the x-ray and compensate for some of the surface damage caused by

any deterioration.

Finally, I asked Iain what he thought of the acetate and

glass material as a whole. He said:

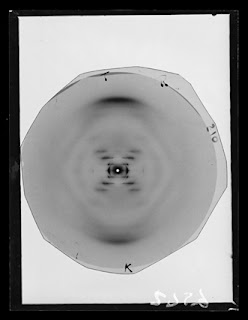

“ I found the material

quite interesting…I’ve learnt more about DNA than I have since school,, good

thing about my job that I don’t have to concentrate on one specific thing.

X-rays of DNA, diffraction, very interesting. They would definitely make a good

print, stretched over a canvas, especially one of the really clear ones like

‘Photo 51’”

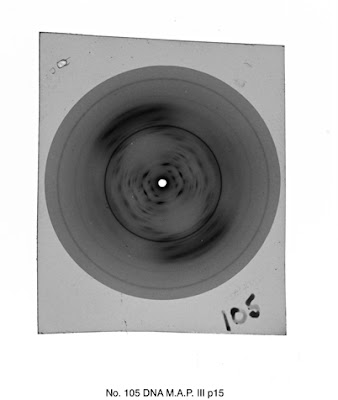

I agreed, diffraction patterns such as ‘Photo 51’ are

visually striking though I personally am more in awe about the crystalline

A-form DNA pictures as there is something rather mesmerising about the symmetry

of these patterns. You can judge for yourself however, as these two x-ray

patterns are shown below.

|

| A-form DNA |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)